The most previous post got me to thinking about the portrayals of college professors in film and on television. I suppose one could write a serious, scholarly article on the topic, but that also seems to suck all the fun out of it. Below is my list. My criteria was pretty lose. I had to have seen the film and the character had to have been a professor at a college or university even if the story line was about another activity, which is true about a lot of them.

Turns out Hollywood finds college professors a pretty interesting lot. No wonder people keep enrolling in graduate school despite the dire economics of it all! We do all sorts of things from dating Jennifer Anniston to finding the Holy Grail, and helping win the Cold War to documenting the nature of human society for aliens from outer space. Enjoy:

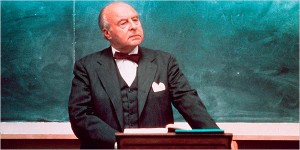

Houseman won an Academy Award as best supporting actor for this role. A writer, director, and producer, Houseman was the director of the drama division at The Juilliard School. His students included Kevin Kline, Patti LuPone, Mandy Patinkin, Christopher Reeve, and Robin Williams. Kingsfield was first major acting job. At least one of his former students said Houseman was not acting. The thing that is different about this role from most of the others on this list is that that Kingsfield's main activity on screen is teaching. It also is probably the most realistic portrayal of a college professor.

9) Professor Terguson (Sam Kinison) Back to School (1986)

9) Professor Terguson (Sam Kinison) Back to School (1986)

Kinison's role in this film is quite small, but Terguson makes this list mainly because he is a historian. Kinison was a stand up comic, and in his main scene, he delivered his lines in the screaming style that characterized his night club routines:

Terguson: You remember that thing we had about 30 years ago called the Korean conflict? And how we failed to achieve victory? How come we didn't cross the 38th parallel and push those rice-eaters back to the Great Wall of China? Then take the fucking wall apart brick by brick and nuke them back into the fucking stone age forever? Tell me why! How come? Say it! Say it!

Thornton Melon: All right. I'll say it. 'Cause Truman was too much of a pussy wimp to let MacArthur go in there and blow out those Commie bastards!

Professor Terguson: Good answer. Good answer. I like the way you think. I'm gonna be watching you.

Thornton Melon (to the camera): Good teacher. He really seems to care. About what I have no idea.

8) Robert Langdon (Tom Hanks) The Da Vinci Code (2006) Angels & Demons (2009) and Inferno (2016)

8) Robert Langdon (Tom Hanks) The Da Vinci Code (2006) Angels & Demons (2009) and Inferno (2016)

In Dan Brown's novels and the films, Langdon is a professor of religious symbology at Harvard University. There is no actual field of "religious symbology." What Langdon does is really art history. Does not sound as cool, though.

7) Richard "Dick" Solomon

(John Lithgow) 3rd Rock from the Sun (1996-2001)

7) Richard "Dick" Solomon

(John Lithgow) 3rd Rock from the Sun (1996-2001)

Solomon is a professor of physics at Pendleton State University in Rutherford, Ohio and shares an office with Mary Albright, a professor of anthropology. I always wondered how small Pendleton had to be for professors from such different fields to be sharing an office. The other thing is that Solomon is an alien sent to Earth to observe the human race. Lithgow is hilarious in the role and won three Emmy Awards. Of course, he might have had some help. His wife is a history professor.

6) Jack Ryan (Alec Baldwin) The Hunt for Red October (1990)

6) Jack Ryan (Alec Baldwin) The Hunt for Red October (1990)

The question is which Jack Ryan?: Baldwin's, Harrison Ford's, Ben Affleck's, or Chris Pine's. I will go with the original, even though all the things Ryan has done by 31 (Baldwin's age at the time) is pushing the limits of believability: CIA analyst, U.S. Naval Academy history professor, published historian, Ph.D. from Georgetown, a Wall Street trader who made $8 million before going to grad school, and U.S. Naval Academy graduate. (His undergraduate alma matter is a major difference between the films and books). But

The Hunt for Red October has a great line that is from the original novel:

Capt. Marko Ramius: What books did you write?

Jack Ryan: I wrote a biography of, of Admiral Halsey, called The Fighting Sailor, about, uh, naval combat tactics...

Capt. Ramius: I know this book!

Capt. Vasili Borodin: Torpedo impact...

Capt. Ramius: Your conclusions were all wrong, Ryan...

Capt. Vasili Borodin: ...10 seconds.

Capt. Ramius: ...Halsey acted stupidly.

5) Ted Mosby (Josh Radnor) How I Met Your Mother (2005-2013)

5) Ted Mosby (Josh Radnor) How I Met Your Mother (2005-2013)

Theodore Evelyn Mosby is an architect living and working in New York, New York.

How I Met Your Mother is the story about how he found his wife. Mosby is telling the story in flashback mode. In the nine seasons of the television program, he dated 38 women, before finding "the one." In season four his fiancé leaves him hours before the wedding for her son's father. In an effort to make things right, her once again boyfriend uses his family connections to get Mosby a job as a professor of architecture at Columbia University as a consolation prize. Mosby teaches at Columbia even though he only has a bachelor's degree. (He must of been some type of adjunct). As it turns out, he and his future wife see each other for the first time when Mosby accidentally enters the wrong classroom on his first day of teaching. As a professor, his students tend to act as something of an entourage.

4) The Professor (Russell Johnson) Gilligan's Island (1964-1967)

4) The Professor (Russell Johnson) Gilligan's Island (1964-1967)

Roy Hinkley, Ph.D. apparently liked Los Angeles and the Dallas/Forth Worth area. He has degrees from USC, UCLA, TCU, and SMU. Cool, calm, and rational, he took a lot of books with him for a three hour tour. The Professor was a learned man and a master of many fields of science, but some things were beyond him. In the 1987 movie

Back to the Beach, Bob Denver played the "Bartender" who was Gilligan in everything but name for legal reasons (the "Bartender" even dressed like Gilligan), and delivered this line:

You know, I lived with a guy for years. A real genius. He could take a couple of these pineapples or a couple of coconuts with some strings and wire and make a nuclear reactor. But he couldn't fix a two-foot hole in a boat. Wanna hear the rest?

3) Peter Venkman (Bill Murray) Ghostbusters (1984) and Ghostbusters II (1989)

3) Peter Venkman (Bill Murray) Ghostbusters (1984) and Ghostbusters II (1989)

Venkman loses his job at Columbia University early in the film--apparently he did not have tenure--and the dean makes the reasons for his dismissal clear:

Doctor... Venkman. We believe that the purpose of science is to serve mankind. You, however, seem to regard science as some kind of dodge... or hustle. Your theories are the worst kind of popular tripe, your methods are sloppy, and your conclusions are highly questionable! You are a poor scientist, Dr. Venkman!

Venkman then goes on to fame as the leader of the Ghostbusters and saves the city from Gozer the Gozerian, a Summerian god who comes in the form of the Stay Puft Marshmallow Man.

2) Ross Geller (David Schwimmer) Friends (1994-2004)

Friends

2) Ross Geller (David Schwimmer) Friends (1994-2004)

Friends was one of the funniest shows on television and dominated the 1990s. Ross has a Ph.D. in paleontology from Columbia University at age 27, which is possible, but just barely. At times Schwimmer's portrayal struck me as quite realistic; Ross seems a bit "over devoted" to his field, and is a bit sensitive when people did not treat his title of "doctor" with the same level of respect that they would give a physician, On the other hand, all he seems to do is hangout with his friends at the local coffee shop, and has a really healthy social life for an academic--he got married and divorced three times and slept with lot of other women. People have done studies, and come up with numbers ranging from 14 to 17, which is twice the supposed national average.

1) Henry "Indiana" Jones, Jr. (Harrison Ford) Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984) Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989) and Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (2008)

1) Henry "Indiana" Jones, Jr. (Harrison Ford) Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984) Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989) and Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (2008)

Not many people know this but Indiana Jones has been played by 7 actors in the 4 films and

The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles, an American television series that lasted for 4 seasons. Despite that fact, Harrison Ford is the actor most associated with this role. In 2003 the American Film Institute ranked Jones as the second greatest cinematic hero of all time. He got his Ph.D. in archeology at the University of Chicago and teaches at Marshall College in Connecticut. He seems to be a specialist in a number of time periods and locals, which is super unrealistic. But how many of us get to see God evaporate a professional, academic rival into nothing?